Humanity's relationship with torture has always been a complicated one. Ancient civilizationsused torturein much the same way some cultures use it today: to gain information, to punish wrongdoers and sometimes just for sadistic pleasure. And it's even been a part of U.S. policy. After 9/11, CIA "black sites" were set up around the world where suspected terrorists were subjected to all sorts of abuses — waterboarding perhaps the one most well-publicized. But the Obama administrationoutlawed all of itin 2015.

But is there any evidence that these macabre methods actually get results? Stuff They Don't Want You To Know hosts Ben Bowlin, Noel Brown and Matt Frederick dig deep for answers as they take a grisly trip through the past, present and future of torture in this episode of the podcast,From the Past to the Modern Day: Does Torture Actually Work?

Advertisement

Editor's note: Before tuning in to the podcast, please be aware that it includes graphic descriptions of torture methods used in ancient Samaria all the way to today's modern military regimes. Proceed with caution.

There's something to be said for the creativity found in humans' ability to be cruel. From crucifixion and the head smasher to the Iron Maiden and coffin torture, humans have figured out, um, interesting ways to get people to talk. Though torture was widespread and not limited to any one country in the 20th century, the mass casualties from both world wars, harrowing tales from Naziconcentration campsand widespread torture by communist regimes during the Cold Warcaused a shiftin how torture was viewed. In 1984, the United Nations filed theConvention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment条约,其中包含官方的定义,and ban on, torture.

But the U.N. ban has its limits. Thedefinition, according to the U.N.does not include "pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions" — that is, the starving of a civilian population, for example, due to economic sanctions. It also only frowns on state-sponsored torture, so any official with any government who wants to inflict violence for a purpose shouldn't be able to. However, it's an easy enough loophole to wiggle through.

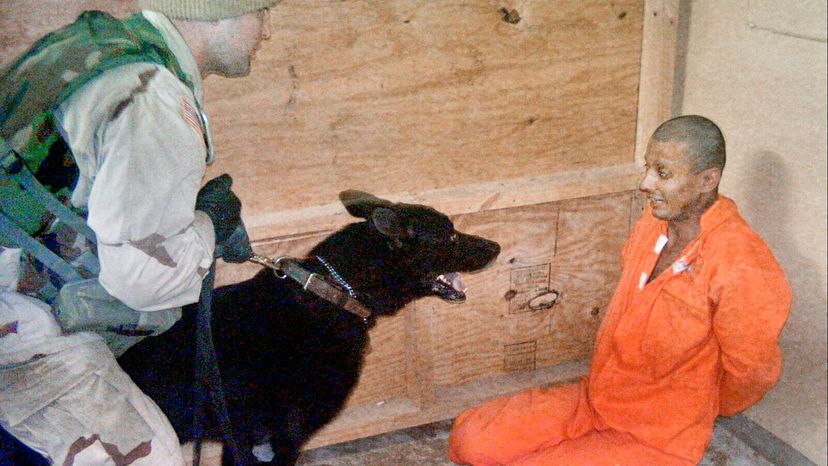

The definition has led to some interesting wordplay. During the George W. Bush administration, prisoners inGuantanamo Baywere being waterboarded, which the Bush administration referred to as "enhanced interrogation techniques" rather than torture. Tricks like this have enabled many governments — including the U.S. government — to get around the U.N. ban. Governments claim to be too civilized for torture, but still are willing to OK atrocities like those we saw atAbu Ghraib.

Could these acts be forgivable, or even welcomed, if these "enhanced interrogations" led to solid intelligence that prevented an attack that killed thousands of people? Perhaps. But according to interrogators甚至the CIA,torture does not workto get reliable information. Most likely those under such extreme duress will say whatever they think interrogators want to hear to get the torture to end. Even if that person does give up some information, their memory could be corrupted by the stress. And that's just assuming the right person is in custody in the first place.

So why do governments still use torture? What is the appeal? Why do they think it's effective? And with so much advanced technology and psychological tools, what is thefuture of torture?Listen to the entire podcastwith Ben, Noel and Matt as they take on all these questions.

Advertisement